Factoring: Post-COVID-19 effects and the potential impact of federal infrastructure plans

Updated June 29 from insights first published June 17

To set the stage: Factoring is the act of obtaining funding – generally from a non-bank entity – by assigning or selling certain present receivables to that entity by a seller, whether a business-to-business and/or a business-to-government enterprise. In return for the transfer or assignment of these accounts, the factor advances funds to the seller in some percentage of the total assigned receivable value (generally 80% to 90% of the total account value), holds the receivables while the account ages, and remits the balance (also known as the reserve) once it has successfully collected the account in full, minus a fee on the capital deployed. A company may decide to engage a factor because of its financial situation, its industry’s situation, and/or the economy at large. Companies may use factoring to address seasonal fluctuations, slow-paying customers, rapid growth, insufficient financial track records, and/or inadequate ratios to qualify for traditional lending. Factors and other sources of small business funding are integral to the U.S. economy.

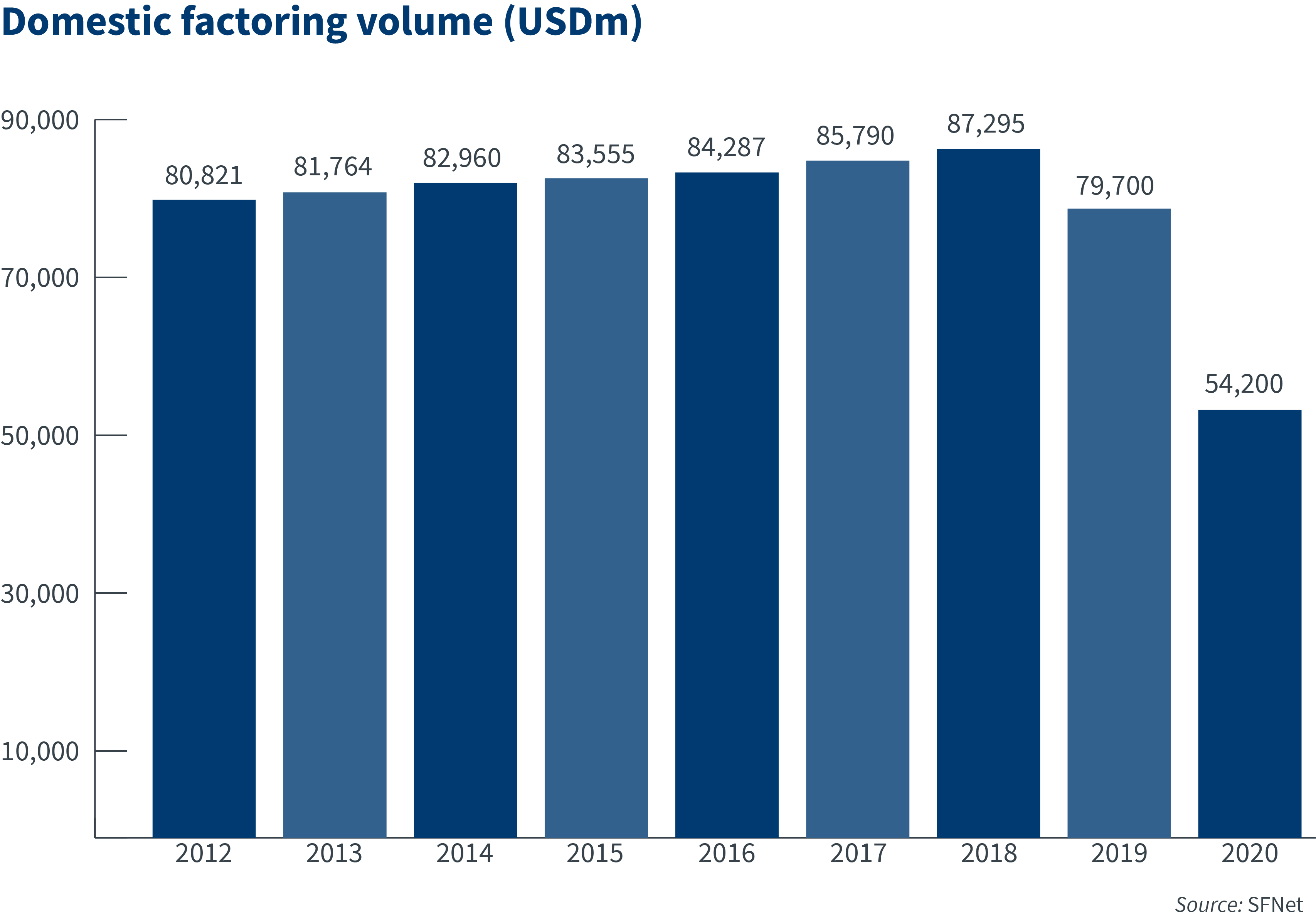

2020, and 2021 thus far, have not been kind to factors. To quantify this, U.S. domestic factoring volume plunged 32% in 2020 alone (see the graph below). In 2004, with $12 trillion in GDP, factoring volume was at about $82 billion, according to Mark Mandula of United Capital Funding. Today, with $20 trillion in GDP, factoring volume is at about $54 billion.

How has COVID-19 had such a negative impact on factoring? The answer lies in the government funding that has been put into place to stimulate the economy during, and emerging from, COVID-19. Unfortunately for factors, and other small to mid-size business capital providers, the government has become a top competitor with the implementation of forgivable programs and essentially zero-cost money. Consequently, factors are now competing with their own tax dollar to find business. Of course, as the stimulus subsides, factors will have a better chance of reeling in new customers. However, currently, there is a lot of money circulating so the need for factoring has certainly decreased.

The federal government’s plans for large-scale infrastructure spending could help pull factoring out of this rut. The current proposed plan, the Bipartisan Infrastructure Framework, has a total proposed spend of $1.2 trillion focused primarily on physical infrastructure projects, with $579 of that new spending, including $312 billion for transportation (including roads, bridges, public transit, and more), $73 billion for power infrastructure, $65 billion for broadband infrastructure, and $55 billion for water infrastructure, among other uses, according to a White House fact sheet.

The federal infrastructure plan’s (or plans’) ability to increase factoring is wholly dependent upon how the government decides to structure the final plan and the extent of private investment. If the government decides to fund the plan solely via taxes, factors may not see a shift in demand for their services.

It is likely, however, that the private sector will play a key role in fulfilling plan goals due to the private sector’s ability to complete projects more efficiently and at a lower cost. One method of private investment would be to partially fund the plan through public-private partnerships (P3s). In this scenario, factors may see a heightened demand for their capital, especially from companies that fall under the “infrastructure” veil. The fact sheet for the current Framework does mention P3s among its “proposed financing sources for new investment,” and the issuance of bonds is listed as well.

P3 arrangements are something common in Europe and in Canada, but the structure has been infrequently utilized within the U.S. With a P3 contract, contractors work directly for private parties in lieu of federal agencies. The private party will often own the project during construction and then return it to the government at some predetermined date after completion, according to a Law360 article. In the past, states have been more open to the concept of P3s than has the federal government, with Florida and Texas leading the pack. Law360 gives a state-level example where Florida used P3 for an Interstate 595 project and the Port Miami Tunnel project, which involved building a mix of tunnels, roadways, and bridges to disperse the flow of traffic. In the Port Miami Tunnel case, a private partner will return the project to the Florida DOT in 2044. Generally, federal infrastructure makes use of individual states’ DOT, but the government has an opportunity this time around to come through with a more focused bill in which it has states, such as Florida and Texas, to model after.

The use of funding through P3s would allow the government to attenuate the future need for corporate tax hikes and/or lessen the deficit over the infrastructure plan’s time horizon (eight years for the current Framework), both invaluable scenarios that would help American citizens and companies succeed long term. Furthermore, the P3 structure would be particularly effective now during the run-off of the pandemic due to its potential to create jobs.

Looking back to factoring, the utilization of P3s would greatly allow factors to get back on their feet through funding the private parties called upon to work alongside the government. Specifically, factors could get their feet in the door with companies involved in construction, water infrastructure, clean energy, broadband and internet, and more, as well as all of their suppliers. I believe factors and numerous other capital providers will begin shifting their focus to infrastructure as this investment in America inches closer to passing.

Contact

Let’s start a conversation about your company’s strategic goals and vision for the future.

Please fill all required fields*

Please verify your information and check to see if all require fields have been filled in.

Inside Infrastructure: U.S. Infrastructure Plan Resource Center

American Rescue Plan Act: Tax Provisions, Grant and Loan Program Updates, New Funding, and More

Related services

This has been prepared for information purposes and general guidance only and does not constitute legal or professional advice. You should not act upon the information contained in this publication without obtaining specific professional advice. No representation or warranty (express or implied) is made as to the accuracy or completeness of the information contained in this publication, and CohnReznick, its partners, employees and agents accept no liability, and disclaim all responsibility, for the consequences of you or anyone else acting, or refraining to act, in reliance on the information contained in this publication or for any decision based on it.