Optimizing an organization with disparate commercial and federal business interests

Many predominantly commercial FORTUNE® 1000 companies have one or more business units that offer goods or services to the U.S. government. In some firms, those units sell to the federal government in precisely the same manner that they would sell to their commercial customers. They often offer goods, as opposed to services, but some offer services as well. The method of their sales is usually by a catalog price, a “brand name or equal” fixed price bid, or an offering under a General Services Administration (GSA) multiple award schedule contract. Such firms operate very successfully under a single, general purpose ERP system.

Many other federal contracting business units offer goods or services via negotiated contracts. Negotiated contracts require the contractor to conform to specific procurement and cost accounting practices that are compliant with the rules and regulations of the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR). They are also frequently required to comply with Cost Accounting Standards (CAS).

The distinction between FAR and CAS requirements is deceptively simple. The FAR controls both the type and amount of costs that are “allowable” under federal contracts. The CAS controls how those costs may (and may not) be “allocated” to federal contracts. For business units that perform the predominance of their contracts for the Department of Defense (DoD) or for another agency that utilizes the services of DoD to perform their contractor audits, there is one more very important set of guidelines: the audit manual of the Defense Contract Audit Agency (DCAA), the Defense Contract Audit Manual (DCAM).

Many of the “allowability rules” have little or nothing to do with prudent business practices. The rule prohibiting the allocation to federal contracts of any costs associated with alcoholic beverages, for example, is purely an attempt to legislate morality. And yet, the consequences for even an inadvertent violation of the prohibition can be a fine of $10,000 per occurrence. The prohibition of allocation of interest expense to federal contracts is intended simply to provide an incentive for contractors to self finance, but it effectively lowers margins by a significant percentage for many contractors. Similar prohibitions against lobbying, marketing and public relations, gratuities and contingent fees make costs that would be considered normal and essential in the commercial world, are unallowable and potentially criminal if charged―even indirectly―to a federal contract.

Compliance with these complex and sometimes arcane rules is both expensive and time consuming. For federal contractors, it is simply a cost of doing business; one that the U.S. government not only recognizes, but insists that contractors incur. If a firm was purely commercial, it would never voluntarily observe the federal rules and regulations. The cost of doing so would be an unnecessary expense and the time and effort required would be a distraction from the firm’s core competency. For firms engaged in federal contracting, compliance is an imperative and the consequences of noncompliance are severe.

Practical Approaches

Firms often choose to segregate their federal business to build walls. Those walls are intended to limit the reach of federal auditors, and are used to be more competitive in the federal space. The walls also isolate the employees and contracts of which more stringent compliance is required and to relieve the commercial performance teams of compliance requirements that do not apply to them. Those same walls tend to limit collaboration and cooperation between the federal and commercial units, and make the sharing of resources more difficult. Increased economies of scale in business functions like information technology, human resources, payroll, facilities administration and maintenance are a significant part of what makes large firms more competitive than smaller companies. Preserving the economies of scale achieved by centralizing such functions is important and requires specific strategies in companies that segregate their federal and commercial units. Since the cost of these functions will be allocated to both federal and commercial units, they will be subject to audit, but the level of scrutiny can be limited.

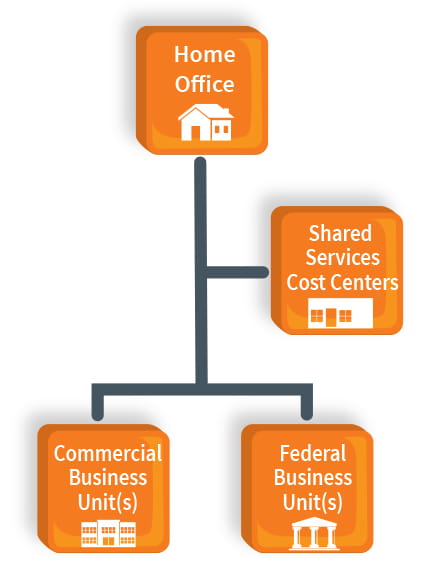

A schematic diagram of a segregated organization may help facilitate a discussion of how the organizations differ, and how they might be affected from examination by federal auditors. In an organization, like the one on the right, the Home Office would accumulate only what are called “residual costs” and they would be allocated by the FAR three-factor formula.

Audit of the Home Office organization would be limited to transaction sampling to assure that the allocation contains no unallowable costs. Segregation of allowable and unallowable costs is required; “unallowables” should either be retained at the corporate level and not allocated, or separately allocated and identified as unallowable. The Home Off ice organization should not perform billable contracts, so there should be no requirement to segregate direct and indirect costs (all costs should be indirect). The employees of the Home Office organization might not even submit timesheets except for paid absence accounting.

A few firms elect to maintain a single unified workforce with federal and commercial contracts comingled across the enterprise. Firms that take this approach benefit from reduced constraints on resource sharing, collaboration and cooperation, but the price of this benefit is the adoption of federal contract-compliant policies and practices across the entire organization. The price can be considerable. Firms that elect this approach are rarely in the FORTUNE® 1000 and would normally work predominantly with the public sector.

A significant number of firms with mainly commercial, but significant federal contracting business units address this major dichotomy by addressing their disparate business requirements with different policies, practices, systems and tools. While effective, this approach raises barriers to effective collaboration, cooperation and resource sharing.

Accounting and auditing of shared services

In large firms, shared services cost centers may include functions like facilities management, human resources administration, payroll processing or information technology services. Often the allocation base is different depending on the function. Facilities management, for example, is often allocated based on square footage occupied by organizations. Human resources administration and payroll processing services are sometimes allocated based on headcount. In fact, they are sometimes combined for allocation purposes for that very reason. IT services may be further broken down by function with different allocation bases. Help desk services or desktop support is sometimes allocated based on some measure of services rendered such as calls answered or “trouble tickets.” Hardware usage allocations are often head-count based, but some firms track equipment usage down to the individual level and attempt to charge actual costs.

Shared services cost centers would be audited to the extent necessary to:

- Ensure that unallowable costs are not included in allocations,

- Confirm the accuracy of the selected allocation base (to assure there is no distortion of the allocations between federal and commercial contracts),

- Confirm the appropriateness of the base selected, and

- Confirm that the services for which the costs are allocated are being provided to all organizations receiving an allocation of costs.

Timekeeping records and systems would be examined only to the extent required to accomplish these objectives. Like the Home Office in the diagram, the shared services cost centers should not perform billable projects and should, therefore, have no requirement to segregate direct and indirect costs or to account for costs by project. That said, many IT organizations do track internal projects when the requirement is outside the scope of normal IT support, and charge the cost of those services directly to the organization that benefits from these services.

The federal and commercial business units would be the only organizational entities in this schematic that would generate revenues and bill clients.

The federal unit would be subject to full audit by the Government with all the mandates of the FAR and its agency-specific supplements, the CAS, the Service Contract Act, all the timekeeping requirements of the DCAA and their audit manual (the DCAM), the prohibitions of the U.S. code with respect to lobbying, gratuities, contingent payments, and the Truth in Negotiations Act. The federal unit would be required to make an annual Incurred Cost Submission (ICS) to its cognizant audit agency, periodic submissions (at least annually, but usually three or four times a year) of proposed, revised or final provisional rates, and periodic submission of a CAS Disclosure Statement. And, of course, every invoice on every federal prime contract would be subject to both pre- and post-payment review including reconciliation of all direct costs claims to the books.

The commercial unit would be subject to audit only to the extent necessary to confirm the accuracy of counts and amounts used to allocate Home Office residual costs and costs associated with shared services cost centers.

Accounting and auditing of shared personnel

If a firm elects to segregate its federal business, no person assigned to a commercial business unit should ever charge directly to a federal contract (or any other project within a federal business unit). As soon as a commercial unit employee includes on his or her timecard a charge number that will result in costs to a federal contract, every aspect of that commercial organization from the timekeeping system to FAR and CAS compliance becomes subject to federal audit. That being the case, the natural question is, “How do large firms with a mix of federal and commercial business leverage their human capital across the enterprise?”

In the process of preparing this paper, we relied on extensive conversations with executives of large firms with both federal and commercial business. We also talked with compliance managers in those firms and our own consultants who have worked with such firms to implement ERP systems or address governance, risk and compliance issues.

Out of those conversations, we identified three alternatives commonly used for management of human resources across a mixed enterprise.

- Maintain a unified global workforce and adopt federal Government-compliant accounting and contracting practices across the enterprise. This approach would permit the firm to freely “borrow and lend” employees between business units with or without revenue transfers. This approach seems somewhat rare.

- Segregate the federal contracts in one or more separate business units and use a formal personnel transfer to move employees between federal and commercial units as required. To be effective, this practice requires that the firm maintain a “common paymaster” system under a single tax ID to facilitate the transfers. In fact, it is this practice that gives rise to the “payroll processing” service center concept. This approach is uncommon, but not rare.

- Segregate the federal contracts in one or more separate business units and let the units deal with each other on an “arms-length” basis. This approach is the most common of the options, but it creates a considerable disincentive to share human capital resources because of the administrative burden involved. Transfer pricing is also an issue and is often addressed using published “catalog pricing” for services or a formal competitive process in which the commercial unit may choose to participate or not.

Option one has the most flexibility and is often very attractive to consulting firms, but it is the highest cost alternative. It is used most often when the federal business is much larger than the commercial business. Companies that use this approach frequently employ a purpose-built, GovCon-specific accounting solution―and a Government contract compliant timekeeping solution― across the entire business.

Option two is found mostly in mid-sized firms or in larger firms with approximately a 50/50 mix of federal and commercial business. These firms will sometimes use a GovCon-specific solution across the enterprise, but more often will use it as a point solution for the federal business and a more general-purpose solution for the commercial business. Companies using this approach sometimes use a GovCon-qualified time & expense solution across the enterprise regardless of the accounting system used in the commercial business because most such solutions may apply different rules to different organizational domains. Use of a common time and expense solution also facilitates the seamless transfer of employees back and forth between business units.

Option three is seen most often in large firms with relatively small federal business and much larger commercial business. These firms often use a GonCon-specific system as a point solution for the federal business and a more general-purpose solution for the commercial business. Companies using this approach sometimes use a common time and expense solution across the enterprise for the non-compliance oriented benefits.

Summary

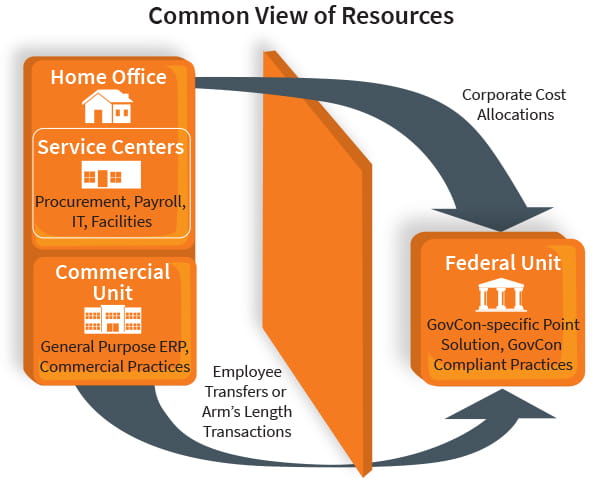

Many large firms are successfully balancing the compliance requirements of federal business units with their need to leverage strengths across the entire enterprise. Our recommendation and one of the most successful approaches for managing challenges for companies with a mix of federal and commercial business is to:

- Create a separation between the federal and commercial businesses;

- Adopt a GovCon-specific point solution as the primary cost accounting system for the federal unit;

- Implement GovCon-compliant practices in (only) the federal unit to meet FAR, CAS and DCAM contract requirements;

- Pass a share of corporate shared services costs to the federal business while maintaining practices designed to limit exposure of the rest of the enterprise to Government audit; and

- Share resources to capitalize on the breadth of capabilities with a combination of approaches:

- Transfer personnel into the federal unit when an assignment is more than short term

- Establish “transfer pricing” for short term resources to facilitate “arm’s-length” transactions

- Maintain an enterprise-wide view of the entire resource pool to manage and source personnel

Some of the most successful FORTUNE® 1000 firms with both commercial and Federal business units have addressed the compliance requirements of their federal contracts in exactly this manner.

Contact

Let’s start a conversation about your company’s strategic goals and vision for the future.

Please fill all required fields*

Please verify your information and check to see if all require fields have been filled in.

Access Our Government Contracting Topic Page for Key Insights & Powerful Tools

Related services

This has been prepared for information purposes and general guidance only and does not constitute legal or professional advice. You should not act upon the information contained in this publication without obtaining specific professional advice. No representation or warranty (express or implied) is made as to the accuracy or completeness of the information contained in this publication, and CohnReznick, its partners, employees and agents accept no liability, and disclaim all responsibility, for the consequences of you or anyone else acting, or refraining to act, in reliance on the information contained in this publication or for any decision based on it.